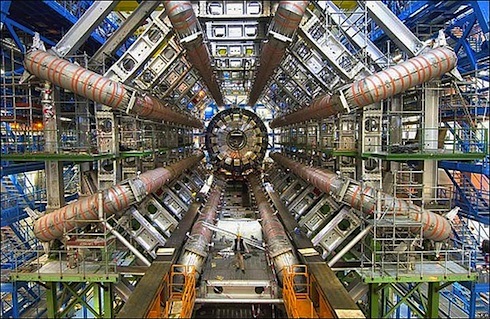

We all wondered if the Large Hadron Collider would create a black hole, but it turns out that it may have instead discovered the very particle it was built to detect. This morning, two teams of researchers at CERN are unveiling results that match the readings they’ve expected to find from the elusive Higgs boson.

The Higgs boson is a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics, which incorporates the set of elementary particles that form all matter and energy in the universe. Some of these are very familiar to us, like photons (light) and quarks (protons and neutrons are made of three quarks each). Others are more exotic and are associated not with matter, but with forces that interact with matter. The gluon, for example, is the elementary particle that carries the Strong Nuclear Force, which binds protons and neutrons together in the nuclei of atoms.

The Higgs boson, meanwhile, is the particle that explains why all the other elementary particles, except the photon and the gluon, have mass. It carries the Higgs Field, which gives mass to any other particles that interact with this field. The masses of the elementary particles is key to our understanding of matter itself, and the Higgs boson is the piece of the puzzle that ties everything neatly together.

So far, the Higgs boson is the only particle in the Standard Model that has not been detected. Tireless searching, first with the Fermilab Tevatron and since at the LHC, has narrowed down the search, but not yet provided any truly convincing evidence. The results announced this morning present around ten candidates for a reliable sign that the Higgs boson is present in the collision debris, out of more than 350 trillion particle collisions. This is far from what anyone would consider conclusive evidence, but would be a major step forward. And no one wants a repeat of the let-down from earlier this year.

Sergio Bertolucci, director of research at CERN, doesn’t want to jump for joy quite yet either. He calls the results not necessarily “evidence” but nonetheless “very interesting.” “It’s too early to say I think we may get indications that are not consistent with its non-existence,” Bertolucci told the BBC, proving that not even high-energy particle physicists can always avoid not using double-negatives.

CERN is currently live-streaming the announcement here and will be providing a more comprehensive summary later today.

Andrew Fleming studied astrophysics at Columbia University before launching into web product development. He likes ice cream. Find him on Twitter.